Jiangnan Style

In the exhibition Translated Traditions – Public Courtyards and Urban Platforms at Aedes Architecture Forum in Berlin, Shanghai’s Scenic Architecture Office shows how it translates traditions.

China locked itself up when the pandemic hit, but that is only “one more reason to look at the country in detail” says Eduard Kögel, a Berlin-based architect, author and curator, and one of the best-informed experts anywhere when it comes to contemporary Chinese architecture. He is right: Architecture is a formidable “bridge” between cultures because it is its own “language” and speaks about society.

Kögel has curated an interesting exhibition at Aedes Architecture Forum in Berlin about the work of Zhu Xiaofeng, who studied at Shenzhen, Harvard and Tongji University before founding Scenic Architecture Office in Shanghai in 2004. To Kögel, he is “one of the roughly 100 good architects in China today.”

China’s regions have unique and distinct architectural styles, so customarily there was a great exchange between architectural cultures within China. The north of the country, including the national capital (since 1949) of Beijing, has traditionally shown a great appreciation of the fine architecture from the Jiangnan region stretching from Nanjing to Shanghai along the southern bank of the famous Jangtse-kiang. During the Qing and Ming dynasties this fruitful region served as a reference point for flourishing agriculture and trade.

When Kögel had to make a decision on which of Zhu's architectural projects to focus of, he chose those in the Jiangnan region, because there is a common denominator weaving these projects together. Since the climate in this central region is moist and mild, the local architecture has developed fine ways of interconnecting house and garden and thus inside and outside.

“In fact, building a house by definition also meant building a beautiful garden,” says Kögel. And this is true for Zhu’s buildings as well: When Scenic Architecture Office design buildings, they give them ample and versatile public spaces in courtyards or vertically layered platforms.

The Bridge of Nine Terraces in Nanjing was designed to be more than a short connection from point A to point B in a new residential neighborhood; it serves as a stage for flea markets and a lookout point where one can enjoy a view of the scenery above the river.

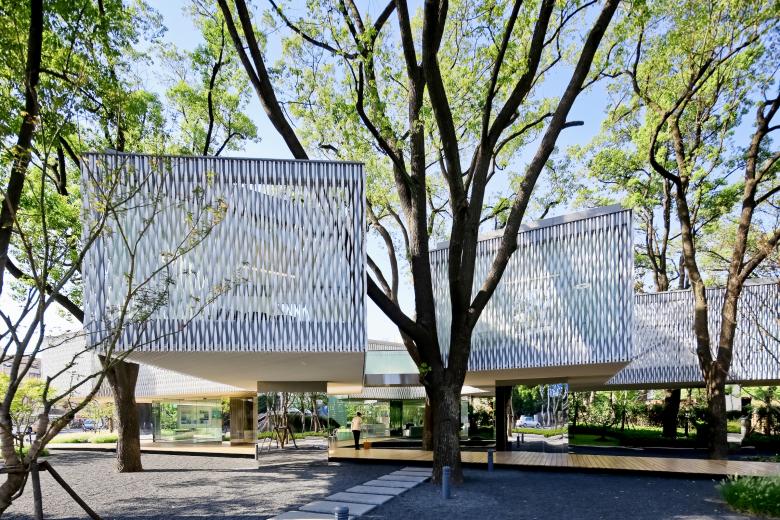

At the Adolescent Activity Center and Civic Art Center in Shanghai’s Pudong district, the staggered open levels create airy shaded places of encounter. While the building itself is huge, the arrangement of smaller huts and boxes underneath and beyond the roof overhangs give the project its human scale. The open-air hallways make the building permeable, giving the architectural design a reasonable and attractive twist that is adapted to the local climate.

This approach unites the nine projects in the exhibition that, for the first time in Europe, provide an insight into Zhu’s thinking. The climate allows the architect to arrange rooms around courtyards, place closed rooms above open but covered platforms, and create lounges and transit spaces that are protected from sun, rain and wind.

Another great red thread in the work (and thus in the exhibition) are the expressive roof shapes Zhu uses. While in the West today flat roofs are often just places to put the cooler equipment, in China (and all of East Asia, frankly) the architecture is still all about the roof. Historians even coined the phrase “roof-only architecture” to describe the simple infill that facades are reduced to in a wooden-skeleton building. The gentle transition between inside and outside and architecture and nature allows for semi-outdoor spaces that can be used year round.

Zhu is good at abstracting and adapting traditional forms, but he is also stubborn about good detailing. The tectonic expression in Zhu’s work is crisp and clear and visually attractive because joints remain readable. “Finding good craftsmen is not always easy in China,” Koegel says, though the same can be said about Europe now, too. That is why many details come to the site prefabricated — just like they did, when the carpenters ruled in Jiangnan’s wooden style of building.

Zhu’s architecture often extends horizontally and integrates well into the surrounding city or landscape. Translated Traditions shows what regionally influenced architecture can be in today’s China. The concept of the exhibition is as clear and elegant as the displayed projects: One nice model, one big photo and one big brochure with details introduce each project. Zhu managed to apply the culmination of the Jiangnan culture from his childhood days to today’s mass society. When China unlocks itself, this blossoming culture deserves to be explored and enjoyed by the world.