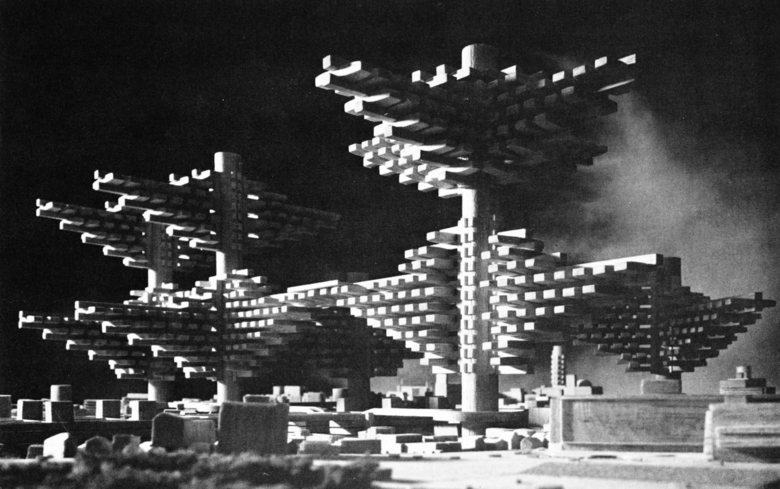

Clusters in the Air, 1962

The March 5th announcement of Arata Isozaki as the 2019 laureate of the Pritzker Architecture Prize brought with it a flurry of official press photos of the Japanese architect's most prominent buildings. But what about the other projects that also define who Isozaki is as an architect – and why he is deserving of the Pritzker Prize?

To see photos of the Museum of Modern Art in Gunma, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, the Nara Centennial Hall, and other important public buildings, check out yesterday's Pritzker Prize announcement. Or scroll down to see projects ranging from before his establishment of Arata Isozaki & Associates in 1963 to unbuilt work this century – ten projects documented with images we found in various corners of the internet.

City in the Air, 1960. While working in Kenzo Tange's office, Isozaki developed a megastructure with large cylindrical cores lifting buildings off the ground. (Image via Misa Shin Gallery)

Oita Medical Hall, 1960. Before he completed the Ōita Prefectural Library (1966, included in the Pritzer media kit and in our announcement), Isozaki realized a Brutalist medical building that he subsequently altered in the early 1970s. Oita, on the island of Kyushu, is where Isozaki's father, a prominent businessman, was based. (Image via Archive of Affinities)

Clusters in the Air, 1962. Isozaki says in David Stewart's "Arata Isozaki Architecture 1960-1990": "Tokyo is hopeless. I am no longer going to consider architecture that is below 30 meters [the city's height limit at the time] ... I am leaving everything below 30 meters to others." (Image via ArtStack)

City in the Air, 1963. Isozaki developed a counterproposal for Marunouchi in Tokyo, which was being demolished by developer Mitsubishi at the time. Tetrahedral megastructures would have sat above the existing buildings as a means of saving them. (Image via Misa Shin Gallery)

Destruction of the Future City, 1968. Displayed at the Milan Triennale in "Electric Labyrinth," which Isozaki curated, the large-scale photomontage depicted a ruined Hiroshima (photo by Shomei Tomatsu) overlaid with irregular space-frame constructions. (Image via Archive of Affinities)

Osaka Demonstration Robot, 1970. Isozaki, working with Tange, designed the Festival Plaza for Expo 70, where various spectacles took place. Two giant robots (Démé and Déku) designed by Isozaki controlled the lighting and set up and disassembled the stage for the different events that took place on Festival Plaza. (Images via cyberneticzoo.com)

Paper model of Teigyokuken teahouse, Shinju-an, Daitokuji, Kyoto, mid-17th century. Isozaki's 1978 exhibition "MA: Space-Time in Japan" traveled from Paris to New York and other cities, explaining the principles behind traditional Japanese architecture and design to other cultures. (Image via Pinterest)

"'Mirage City' – Another Utopia," 1997. The exhibition and workshop at NTT InterCommunication Center in Tokyo was directed by Isozaki and included contributions by dozens of Japanese architects exploring the "process through which a new Utopian idea can take shape." (Image via ICC online archive)

ASKA Houses, 1974-88. These small structures in Karuizawa were the summer retreat for Isozaki and his late wife, sculptor Aiko Miyawaki. The place also was the setting for an interview with Isozaki for the 2018 Time-Space-Existence exhibition. (Image via PLANE—SITE)

Qatar National Library, 2002. The Emir of Qatar was intrigued with Isozaki's early works and wanted him to build something like it for the national library. Isozaki speaks about the project with Rem Koolhaas in "Project Japan," a book of interviews about Japan's Metabolism movement. Ironically, Koolhaas's firm, OMA, would eventually build the Qatar National Library, not Isozaki. (Image via Architectural Lighting Group)