This year's World Building of the Year at the World Architecture Festival in Berlin is a modest rammed-earth dwelling in a Chinese village. What does the win say about WAF and other awards?

For those who have not participated in one of the ten World Architecture Festivals to date, WAF is structured much like a dog show, with numerous “best-in-breed” winners in typological categories like Culture, Housing, and Office moving on to the the “best in show” judging by the so-called Super Jury. The categories fall generally into either Completed Buildings or Future Projects, but most of the attention is given to the former, whose winner is dubbed the World Building of the Year. One thing that makes WAF unique is how the architects who entered the festival and were shortlisted in their respective categories present their projects during the fair, in full view of both a three-person jury and whoever else wants to attend. With this setup, much of the first two days of the three-day festival is spent hopping from one crit room to the next – structured as inflatables beneath the industrial trusses of Arena Berlin – to take in just some of the hundreds of presentations.

On day one of WAF I wasn’t able to watch a crit until 2:40pm, after ten presentations had taken place already in thirteen categories – one every 20 minutes. There was a morning keynote by architect Rafael Viñoly, some work in the press room to write up the talk, a lunchtime lecture by Francis Kéré, and a chat with the organizers of the Arcaid Photography Awards, on which I served as a judge. With some time before the evening keynote to catch a few crits, I grabbed the schedule and ran my finger across the row of 2:40pm presentations. From the dozen crits taking place in that time slot, the one that stood out the most was taking place in bubble 10 in the New & Old Completed Building category: the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s Post-earthquake reconstruction and demonstration project of Guangming Village in Zhaotong, China. Somehow, circumstances led me to sit in first on the project that would become World Building of the Year.

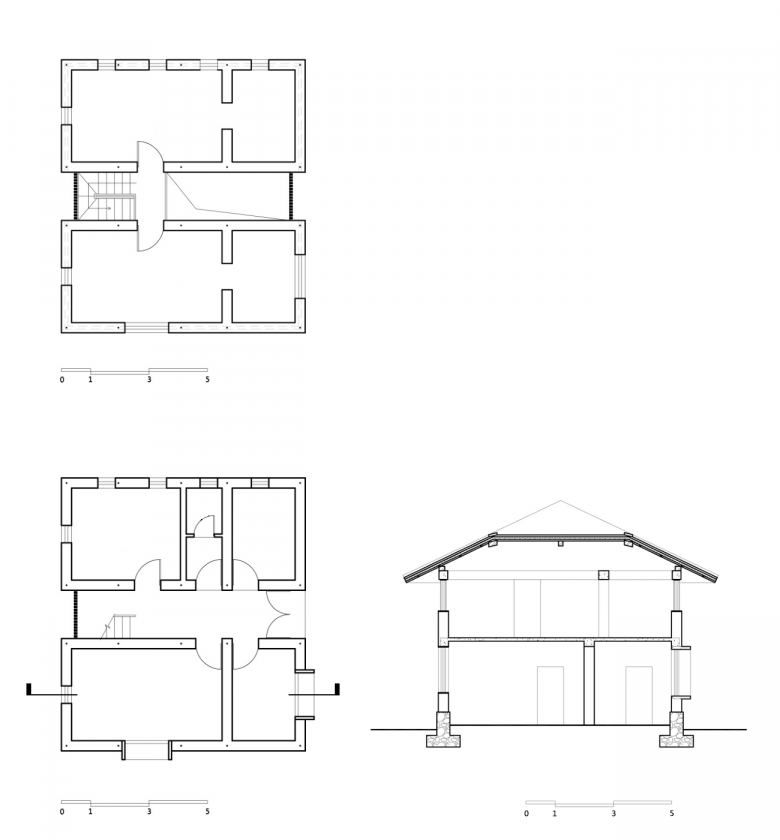

Edward Ng, a Professor of Architecture at the Chinese University of Hong Kong's School of Architecture, presented the project to the three-person jury and a not-quite-packed inflatable with about 25 people in attendance. He explained how 100 million people around the world live in rammed-earth dwellings, many in areas prone to earthquakes. With these types of vernacular buildings susceptible to damage from tremors, the ongoing research by him, Li Wan, Xinan Chi, and their other colleagues at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) and Kunming University of Science and Technology (KUST) has focused on the science and design of earthquake-proof rammed-earth dwellings. A prototype built for an old couple in Guangming Village, which was hit hard by the 6.1-magnitude Ludian earthquake in 2014, is hardly the first building to come out of their research, but it is one that is gaining them recognition. Ng ended the presentation by holding up an issue of Architectural Review with the Guangming Village house on the cover; earlier this year the project won the AR House award, besting fourteen other shortlisted projects.

On day three, when Ng gave a similar presentation to the Super Jury (Christoph Ingenhoven of Ingenhoven Architects, Ian Ritchie of Ian Ritchie Architects, James Timberlake of Kieran Timberlake, Ellen van Loon of OMA, and Mun Summ Wong of WOHA) on the main stage, he was asked about his team’s ambitions to apply their research to other locales all over the world – “twenty down, one hundred million to go,” were Ng’s words during his presentation, referring to the numerous rammed-earth structures they have completed during ten years of research. Specifically, how could a technique rooted in local soils and other local materials benefit from their research? Wouldn’t each locale require new findings? He replied that certain things would need to be studied locally, but the science behind their research could be applied directly to other places. The Super Jury also asked if there were any areas that needed improvement. Ng replied that the design of the concrete ring beam that tops the rammed-earth walls is one such area that needs development, while in the AR House awards the team admitted that the steel reinforcing within the rammed-earth walls did not contribute much in terms of stability so they were looking to bamboo as a replacement. In other words, the house, though seen as a finished product, is actually a mid-point on a continuum of further refinement.

It’s worth making a comparison between the Guangming Village house and another project I observed during WAF, two projects at opposite poles from each other: Heatherwick Studio’s Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCAA) in Cape Town, which was in the running for Culture Future Project (oddly, since the building is now occupied). Although Thomas Heatherwick was not there to present, the crit room was standing room only, with at least a hundred people trying to squeeze into the bubble to watch the presentation, four times as many as Ng's presentation. Zeitz MOCAA’s budget was at least £30 million, small compared to other cultural institutions today, but grand in relation to the rammed-earth house's £5,000 budget, which followed from what the Chinese government gives for the loss of a family home. But the most glaring difference is the role of architecture in each project: Zeitz MOCAA, with its hotel component also by Heatherwick, is an integral part of a transformation of an old industrial section of Cape Town (the building was formerly a grain silo) into a stop for the globetrotting rich. The CUHK/KUST project, on the other hand, aims to provide villagers an alternative to both concrete and brick houses and to moving to nearby cities; in this sense the World Building of the Year is as much a project of preservation (of building technique and way of life) as it is new construction.

Before the 2017 edition of WAF, it was projects like Heatherwick’s Zeitz MOCAA that received all the press (we’re guilty of that too, as the links in the previous paragraph reveal). But being named Building of the Year brings a great deal of attention to the ongoing efforts of Ng and his colleagues, which is great. More than that, the win sends a signal, "that architecture is just as relevant in the poorest of communities as it is in the richest," in the words of WAF's Paul Finch. But also that modesty can be more important than iconicity; that it's not all about cities or size (in China or elsewhere); that process is as important as product; and that every now and then awards manage to reveal the unexpected gems among the usual suspects.