US Building of the Week

44 Union Square

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission often requires that rooftop additions to landmarked buildings are invisible from the street. Such is clearly not the case with this building overlooking Union Square Park. BKSK Architects added a glass dome to the historic home of Tammany Hall, referencing indigenous myths predating the infamous 19th-century political party. The architects answered a few questions about the project at 44 Union Square.

Location: New York, NY, USA

Client: Reading International Inc.

Architect: BKSK Architects LLP

- Partner in Charge: Todd Poisson

- Collaborating Partner: Harry Kendall

- Project Manager: Joe Hogan

MEP/FP Engineer: Dagher Engineering

Lighting Designer: Atelier Ten

Energy and Commissioning Services: OLA Consulting Engineers

Exterior Envelope Engineering: Buro Happold

Preservation/Research Consultant: Higgins Quasebarth & Partners

Geotechnical Engineer: RA Consultants

Client Community Relations Consultant: Capalino+Company

Owner’s Representative: Edifice Real Estate Partners

Contractor: CNY Group

Building Area: 72,000 sf

The commission originated as a limited design competition in 2013. BKSK was invited to participate to reimagine the building for use as commercial and retail spaces. When we received the design brief to join the competition, we were amazed to learn that the real namesake of Tammany Hall was a legendary Native American Chief from the Lenape Nation from the 17th century. The design brief had implied that the owner was ready to move on from the Tammany name, but when we found out the truth behind the name, we decided to propose something that focused on the name Tammany in an unexpected way. We read that the Lenape creation story involves a giant turtle rising from the sea and developed a design to honor the Chief and honor the Neo-Georgian DNA of the building by adding a dome to the building inspired by the form of a rising turtle.

Established as one of the final headquarters of The Society of St. Tammany, the three-story brick, limestone and terra cotta structure known as Tammany Hall was built on the corner of Union Square East / Park Avenue South (then 4th Avenue) and 17th Street in 1928. Designed by the firms Thompson, Holes & Converse and Charles B. Meyers, Tammany Hall’s architectural intent took Greek revival elements from Federal Hall, the US National Memorial on Wall Street and site of George Washington’s inauguration, and the Neoclassical oversized red brick design of Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello.

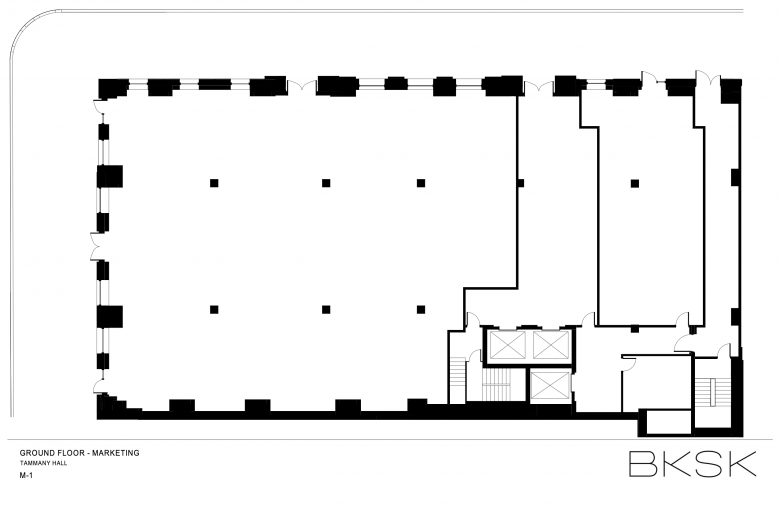

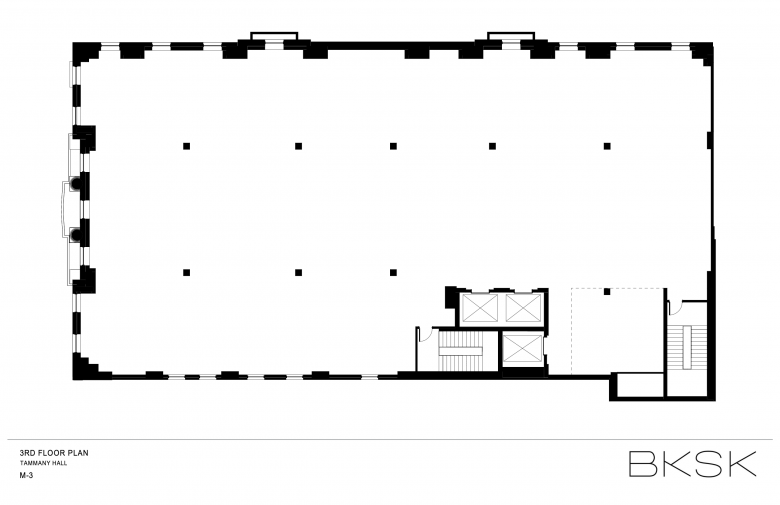

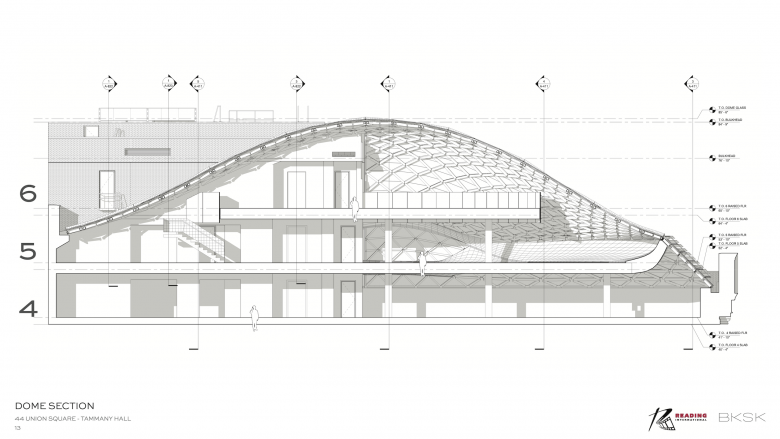

44 Union Square sits prominently at the northeast corner of Union Square Park in Manhattan. Today, a new 70,200-sf, Class-A commercial building with three floors of restored historic street facades, and a glass/steel dome addition, the restorative design was unanimously approved by the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission in 2015. The new building expands the usable square footage of the historic building by 30,000 sf and reimagines it as an iconic anchor to Union Square. The restoration and expansion included preserving two historic facades, new bronze storefronts inspired by the original 1928 design, and a three-story vertical extension composed of a self-supporting free-form shell grid dome atop a reconstructed hipped roof of steel and glass with terra cotta sunshades.

This reinvented building commands attention. Its former life as the last headquarters for the powerful Tammany Hall political organization is apparent in its preserved facades, but the visible rooftop expansion evokes a deeper history, serving as a living monument to the indigenous Lenape people.

The origins of Tammany Hall as a populist organization include its namesake, the legendary Lenape Chief Tamanend. Early in the design stage, BKSK initiated an ongoing consultation with founding members of the Lenape Center to bring an authentic, legitimate voice and representation to the concept of a dome addition inspired by the Lenape creation story of a great turtle rising from the sea. Reflecting the inspiration of the original Tammany Hall’s naming by its 18th-century founders who respected the renowned Chief Tamanend’s willingness to listen to all voices, historic details such as the sculpted medallion of Chief Tamanend’s portrait on the north facade still remain, along with our new homage to Tamanend that crowns the building. While respectful of the building’s historic character, the organic domed intervention provocatively yields insight about the underlying social history of the building as well.

In 2013, Tammany Hall was designated an individual landmark for its “special heritage, and cultural characteristics.” [PDF link of designation] As a preservation approach, it is designed to be deeply thoughtful and yield unexpected insight about the building’s hidden social history. The contemporary steel and glass dome is meant to symbolize Tammany Hall’s long-forgotten background as a populist social club — promoting a voice for all — and alludes to the indigenous leader from whom the building and the society it once housed took their name; the turtle represents Chief Tamanend’s nation, the Lenape.

The redevelopment of Tammany Hall creates a meaningful visual dialogue between contemporary and historic architecture and accommodate change and vertical expansion with historic integrity and a fresh narrative. Capping off the collaboration, the finished project was blessed in a traditional Lenape ceremony acknowledging past and future occupants of the site. The unexpected juxtaposition heightens the perception of the building’s significance, animates the corner of Union Square in a way it never was, and evokes connections to history that are important to both understand and acknowledge.

Decoupling and reattaching landmarked facades are a far less common — and more complicated — way to preserve historic structures when compared with the gut renovation of entire buildings. The success of this project, and the industry-leading companies assembled to deliver the results, presents a tremendous achievement for the architecture, engineering and construction industries. Gut rehabilitations of aging building stock are becoming even more commonplace as empty and available parcels of vacant, commercially zoned real estate are becoming exceedingly rare in New York City.

Preserving the landmarked north and west facades required design innovation and field adaptability to execute. Vertical bracing towers and horizontal steel walers provided lateral support, effectively sandwiching the facade in place. Bracing was further supported by 30-foot-deep piles drilled through the facade brick, secured with steel ties and anchored through the sidewalk. Antique foundations below these exterior walls were preserved.

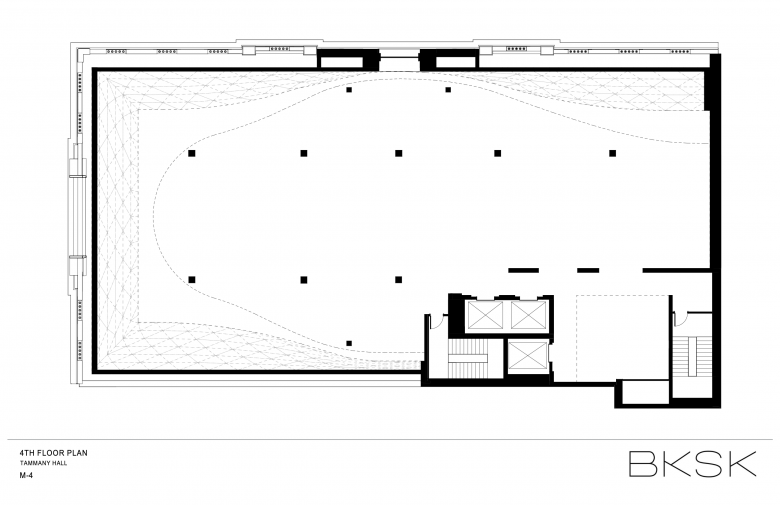

The new building was constructed with reinforced concrete shear walls, a reinforced concrete flat-plate slab floor system. Reinforced concrete walls, a thickened floor slab along the west, north and portions of the south facade, and a fourth-floor concrete corbel structure support the loads created by the dome’s complex geometry.

The preserved facade was reconnected to the new interior core floor-by-floor. New perimeter concrete piers enclosed the facade’s existing steel columns and were attached to floor slabs with welded metal plates. Some bracing was left in place to further support the historic facade’s attachment to the new building.

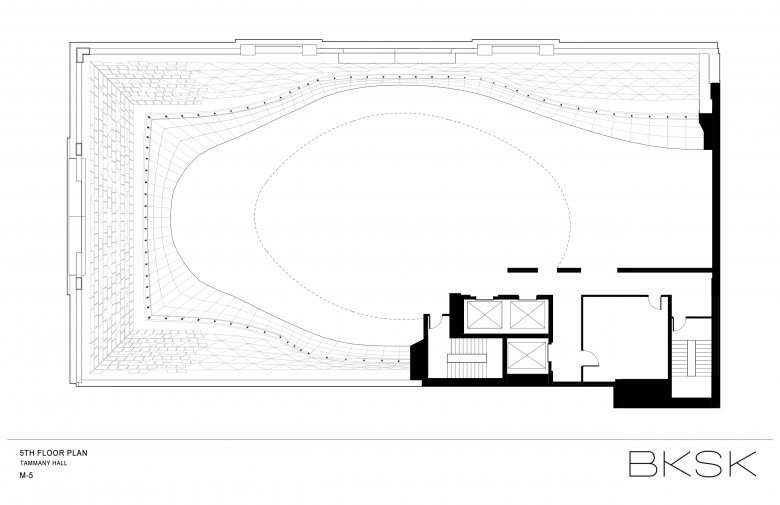

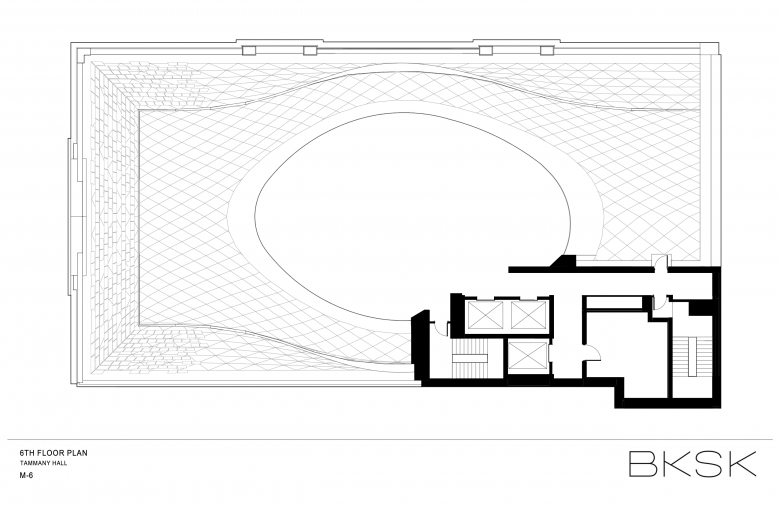

The project expanded usable square feet with the addition of a three story, turtle shell-inspired parametric dome which is the first of its kind in New York City. There are precedents for the addition of a glass dome to Neo-Georgian architecture around the world, but ours went a step beyond using the inspiration of the Lenape creation story.

Creating the dome required a complex construction plan including reinforced concrete shear walls and a fourth-floor concrete corbel to support new loads. The triangulated freeform domed roof structure, consists of steel tube members bolted and welded together at intersecting nodes. We calculated angle and location details to adjust the design of the terra cotta sunscreen at the base of the dome, which recalled the building’s original slate hipped roof. The team’s efforts resulted in a refined dome design, reducing the amount of necessary steel and increasing the size of, and thereby lowering the number of, glass panels required.

All dome components were designed and manufactured in Germany and shipped to a warehouse in New Jersey for short-term storage. Components were delivered to the New York project site in batches of two to four members, two to three times per week, due to the absence of significant lay-down and staging area at the site.

A 14-step process was developed to manage the delivery and installation of each of the 54 uniquely designed and sized primary steel members and more than 750 unique glass pieces. Each had to be crane-set in place and assembled in precise order. Shoring posts were added to the fourth, fifth, and sixth floors to reinforce the dome’s incomplete steel framework as it was assembled, prior to glass installation.

Additionally, rigorous research was conducted to select the glass for the dome which provides climate and light control while offering clear views from inside to the Park and beyond. Solar insulation, light infiltration, and glare probability studies as well as investigation of glass dome precedents informed the glass mapping over the dome structure and the development of sunshades and other glass shading solutions.

Email interview conducted by John Hill.