6 Highlights from the 2022 Whitney Biennial

An Introduction to Nameless Love (2019) by Jonathan Berger (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

The 2022 Whitney Biennial, titled Quiet as It's Kept, opens to the public on April 6 at the Whitney Museum of American Art's Renzo Piano-designed building in New York's Meatpacking District. World-Architects got an early look, finding a half-dozen contributions with architectural angles.

The 80th edition of the Whitney's flagship exhibition was delayed one year due to the pandemic, but it arrives as much of the world is ready to travel and visit places, museums included, that have been closed or been functioning at reduced capacity for the last two years. This edition of the Whitney Biennial was curated by David Breslin and Adrienne Edwards, both from the museum, and although they devised the theme and started working on the Biennal before the pandemic, the racial protests of 2019, and the current war in Ukraine, artworks with strong social messages are prevalent. Even so, with this website's focus on architecture, the artworks below are predominantly engaging from architectural perspectives, be it the way they engage the museum's building, the forms they take and materials they use, or their immersive, spatial qualities.

Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept is on display at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City from April 6 – September 5, 2022.

"Palm Orchard" (2022) by Alia Farid

Even before people enter the Whitney, Alia Farid's Palm Orchard overtly makes itself — and the Biennal — known. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

According to the Kuwaiti artist, the artificial palm trees, "are low-grade stand-ins for the palm groves that once covered large areas" of Basra but were decimated during the Iran-Iraq War, making the installation a commentary on "how nature and landscapes are weaponized, harnessed, and destroyed by governments and extractive industries." (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

The colors and mechanics of the "palms" indicate that this artwork is illuminated, making an evening visit necessary to see the sculptures in their fullest. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

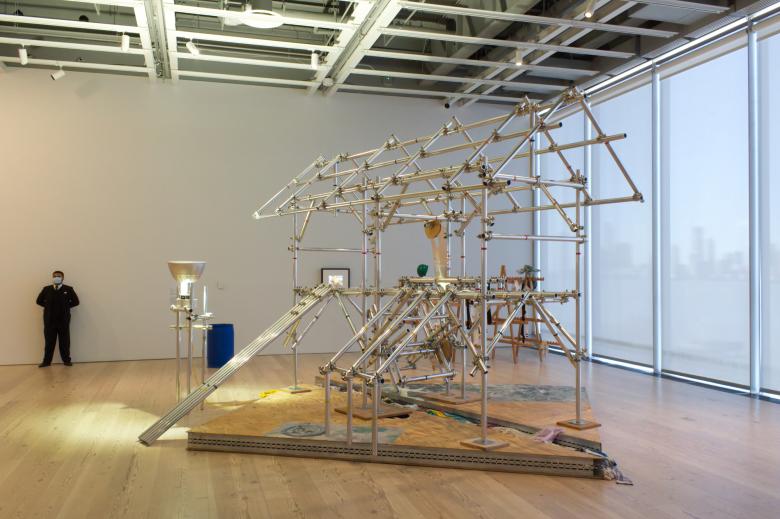

"Sutter's Mill" (2000) by Jason Rhoades

Of the 63 artists in the Biennial, Jason Rhoades is one of thew few who is no longer with us; he died from heart failure in 2006 at just 41 years old. (

The paintings of Denyse Thomasos, who died in 2012, are also a highlight of the Biennal, but unfortunately I did not capture decent photos to include here.) (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Made by Rhoades to resemble the California sawmill where gold was discovered in 1848 setting off the California Gold Rush, the installation also has a performative aspect to it, with its aluminum structure

disassembled and reassembled over the course of a day. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Not shown here but also part of the Biennial is one of Rhoades's readymades: a 1992 Chevrolet Caprice Classic parked in the plaza between the Whitney and the High Line. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

"Untitled" (2018) from the series "Valle San Pedro" by Mónica Arreola

Both the subject of Mónica Arreola's photographs and the armature they are mounted on hint at the fact

she trained as an architect. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

The photographs in the Valle San Pedro series document the 2008 global recession's impact on Tijuana, focusing on developments abandoned mid-construction. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

"A Clockwork" (2021) by Sable Elyse Smith

The four artworks presented here following Palm Orchard are located on the huge fifth-floor gallery of the Whitney, an open space free of partitions; Sable Elyse Smith's A Clockwork is one of the few pieces with a scale on par to its setting. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

The kinetic piece,

which moves like a Ferris wheel, is made from furniture used for prison visiting rooms, a fact that makes more sense accompanied by the artist's video (visible on the wall in the previous photo) of police patrol footage. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

"Kitchen" (2019) by Emily Barker

Next to A Clockwork at the eastern end of the fifth-floor gallery is Emily Barker's Kitchen, which looks like typical kitchen cabinets articulated in clear plastic. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

But the artist, who uses a wheelchair, exaggerated the height of the counters to 5'-9" (the typical height of a man)

to show how "the seemingly mundane built environment and the mass production of objects harms people every day." (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

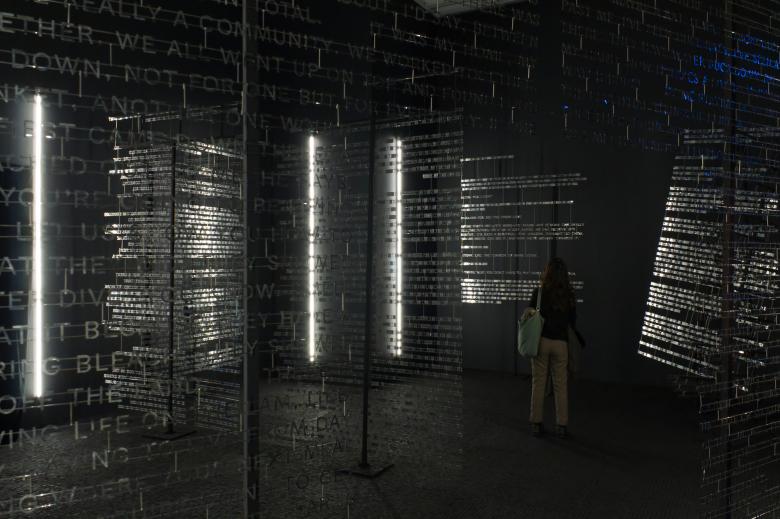

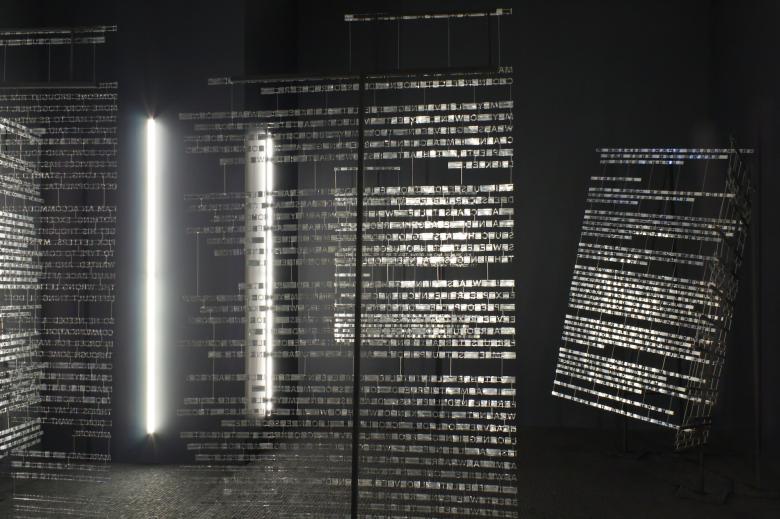

"An Introduction to Nameless Love" (2019) by Jonathan Berger

Inspired by previous Whitney Biennials that featured smaller "shows within shows," the sixth floor — unlike the open fifth floor — has a number of smaller, intimate galleries devoted to single artists, one of them a dark space by Jonathan Berger. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

As displayed here,

An Introduction to Nameless Love features three text-based sculptures that define two small spaces reached by an entryway; visitors traverse a space with floors of loosely laid charcoal tile flooring. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

The texts are dialogues between unhoused people and the artist, expressed in handmade tin letters soldered to supports. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)