On display at Harvard University Graduate School of Design's Frances Loeb Library until October 15, The Book in the Age of … is an exhibition that came out of a research seminar at the GSD taught by architect Rem Koolhaas, graphic designer Irma Boom, and architectural historian Phillip Denny. World-Architects went to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to see the exhibition.

If any architect were to be involved in an exhibition about the past, present, and potential future of books, it is Rem Koolhaas. No architect since Le Corbusier has understood the value and power of books and, more importantly, used them as a form of media integral to their architectural practice like he has. From his first book, Delirious New York in 1978, and the magisterial S,M,L,XL, done two decades later with Bruce Mau, to Project Japan (with Hans Ulrich Obrist) and Elements of Architecture this century, Koolhaas has produced books with a density of information and ideas whose influence has not been approached by any other architectural contemporary.

The last book mentioned above, Elements of Architecture, though it is associated with the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale that Koolhaas directed, is one of numerous printed Koolhaas creations that can be traced back to a GSD studio. Like the earlier Great Leap Forward (2001) and Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping (2002), Elements is a huge book on par with S,M,L,XL, but instead of Mau it was designed by Amsterdam's Irma Boom, who has been the Rotterdam architect's go-to designer for more than twenty years. Their collaboration has yielded books, Project Japan among them, that manage to present reams of data and research and their interpretation in ways that are both understandable and beautiful. Them teaming up for a studio focused on the book was therefore logical.

The Book in the Age of … began as Bookmaking, the VIS-2461 course in the Spring 2023 semester at the GSD. Taught by the team of Boom, Koolhaas, and Phillip Denny, a PhD candidate in architectural history at Harvard, the “project-based seminar” tasked the dozen students* to “investigate histories of print across historical and geographical contexts,” “interpret books in multiple languages,” and “develop their own books” based on their studies of books and bookmaking. The goal? Nothing less than “chart[ing] new trajectories for the future of the book.” As the outcome of the seminar, The Book in the Age of … uses various formats of printed words and images to present a collective history of the book and display a dozen “original conjectures for its future evolution.”

*Bookmaking students: Robin Albrecht, Nour-Lyna Boulgamh, Ilana Curtis, Justin Hailey, Marya Demetra Kanakis, Han Na Kim, Tomi Seyi Laja, Yeonho Lee, Michael Kurt Mayer, Sarah Nicita, Lauren Safier, Samanta Zhuang

The Book in the Age of … the Hand

Following from the seminar, the contents of the exhibition are structured into three chronological phases: the book in the age of “the hand,” “press,” and “machines.” The first object visitors to the Frances Loeb Library encounter is a large “book” in a triptych form, made from poster-size pages folded into metal covers and hinges. The unwieldy object fixed to the table is titled Gutenberg Galaxie III: Atlas of the Book, an explicit nod to The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man, the 1962 book by Marshall McLuhan. McLuhan wrote of “a ‘global village’ populated by a ‘typographic’ human and connected by media,” per the wall text, “at first printed books, and then later radio, television, and the Internet.”

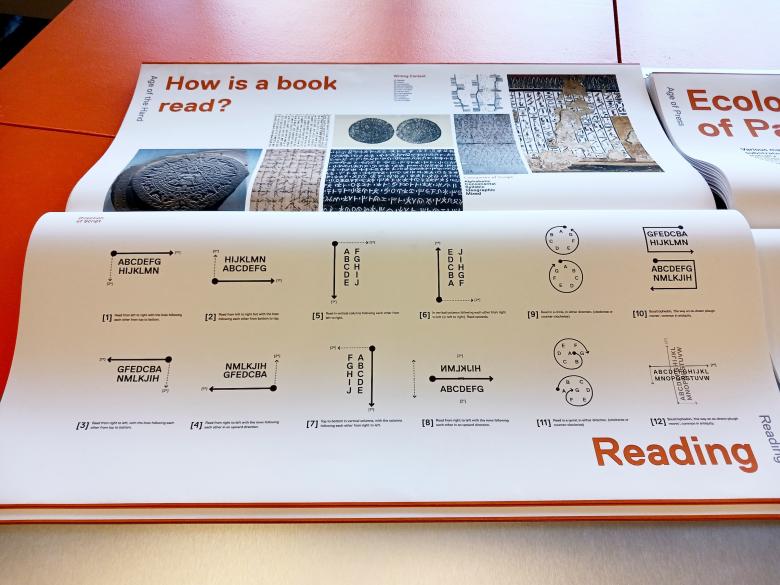

The tripartite structure of the seminar/exhibition is evident in these three volumes arranged diagonally across the table near the entrance, their large ink-jet-printed coated sheets far removed from a typical book. Before getting to Gutenberg and our digital present, one digests the book “in the age of the hand,” although this first volume reaches back to objects that could hardly be called books. In retrospect, the numerous artifacts spanning millennia were clearly integral to the book’s development: inscribed stones, clay tablets, wood boards, metal plates, even palm leaves and ivory. Papyrus, parchment, and other forms of paper eventually prevailed, first as scrolls but then as pages in codices, the immediate precursor to the printed book.

The transfer of information, of knowledge, from one person to others was dependent on tools and labor in this phase, resulting in objects that were more or less singular, far from the mass-produced books we are familiar with today. But in them are the workings-out of how books are read — a fascinating spread displays the ways different languages and characters were laid out (above) — and where books were made and read, such as illuminated manuscripts in medieval monasteries. Books are objects, in other words, but they are also means of expressing human thought and, to a lesser degree, they are elements of social lives.

The Book in the Age of … Press

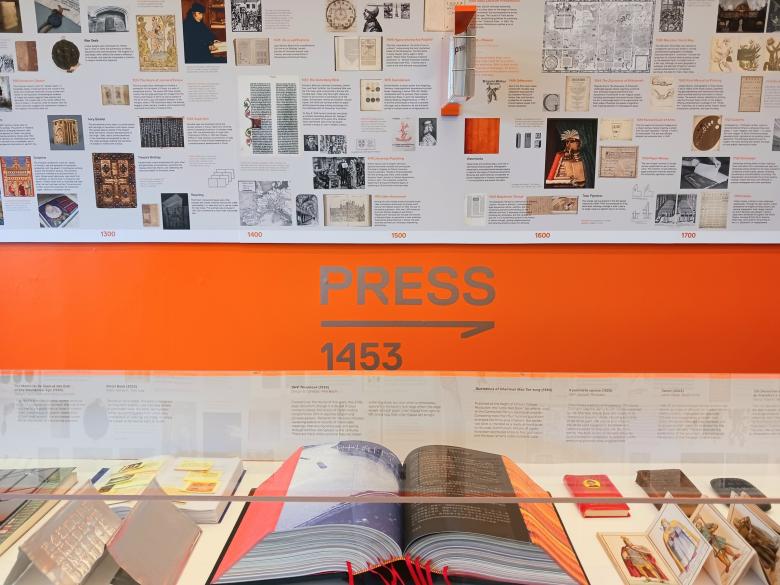

The most important decade in a timeline of books is the 1450s, when German inventor Johannes Gutenberg used movable type (already in use in China for centuries) for letterpress printing, thereby inventing the printing press. The Gutenberg Bible, as it is known, was printed in 1455, the first major work to be printed in Europe with movable type. Of the estimated 135 copies that were made, only 48 copies survive, just twenty of them fully intact. One of those twenty Gutenberg Bibles is at Harvard's Widener Library; this we learn reading a timeline on the wall at the far end of Loeb Library, the second of four (or five, as we'll see) displays that comprise The Book in the Age of …. In one of the spreads of the poster-size book, visitors also realize that the pages of the first printed books “so closely resemble those of manuscript books as to be virtually indistinguishable to the unpracticed eye.” Put another way, by replicating the earlier handwritten manuscripts, the first printers did not yet know how to exploit the full potential of the new technology, a phase akin to the present relative to ebooks and other digital technologies.

In the large book and on the timeline, numerous illustrations and captions describe what transpired in the age of press: intaglio and other printmaking techniques supplanted handmade illuminations; the printing press led Claude Garamond, John Baskerville, William Casion, and other now-familiar names to develop typefaces whose character and legibility depended on the shape of letterforms. Books were starting to take on forms people today recognize, but their production still relied on hand labor, such as the compositors selecting the right “types” to “stick” the sentences for the “galleys.” But the age of machines was drawing near.

The Book in the Age of … Machines

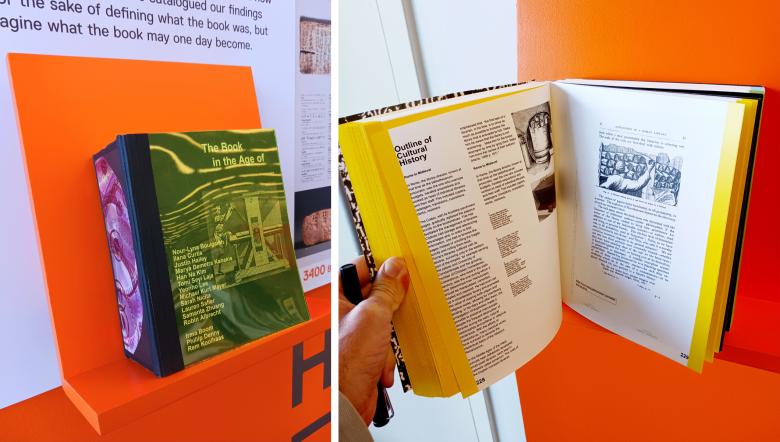

At the start of the timeline on the wall of Loeb Library is a mockup for a book, one whose size is similar to Elements of Architecture but is yet another outcome of the Bookmaking seminar. Sitting on a shelf and affixed to the wall, the book functions more as a display of the voluminous information assembled by the dozen students — “information overload,” in fact, was one of the initial impressions of the exhibition I jotted down in my notebook — than as an element visitors can digest during their brief moments in the library. The mockup clearly expresses both Boom's and Koolhaas's predilection for XL books, but it also conveys the deficiency of an exhibition in the face of so much research, so much information. The brief captions in the three-volume table-book and on the wall are manageable, but they are just a fraction of the story of the book encountered in the seminar.

In the exhibition timeline, the machines take over in 1789, the year that saw the publication of Qu'est-ce que le Tiers-État? (“What Is the Third Estate?”) in France, helping to spur the French Revolution, and The Power of Sympathy, printed in Boston and considered the first American novel. Inventions by Henry Fourdrinier, Louis Braille, and others meant that every part of the bookmaking process — papermaking, printing, binding — was a product of machines. Braille's contribution is displayed in one of the plastic vitrines cantilevered from the timeline: Touch the Universe: A NASA Braille Book of Astronomy, published in 2002 following the imagery captured by the Hubble Space Telescope. While the display of the NASA book and three other books in front of the timeline is clever, the inability to handle books in an exhibition about books is frustrating — a feeling underscored in the next section.

The Book in the Age of … Globalization

Paralleling the timeline is a long vitrine whose contents alternate between notable books (Gregor Reisch's Margarita philosophica ["Philosophical Pearl"; 1517], S,M,L,XL [1995], Irma Boom's SHV Thinkbook [1996], etc.) and “original conjectures” with the seminar's students speculating on the evolution of the book in our age of globalization. Some clear analogies are drawn between old and new, such as the embossed metal cover of MoMA's The Machine: As Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age (1968) sitting next to Robin Albrecht and Tomi Laja's Metal Book (above), which, "devoid of ink or paper," was "designed for long-term stability." Their classmates made 3D-printed books and woven books; they explored what ChatGPT and other AI technologies might mean for books; and they experimented with the format of the book, even crafting a fashionable book bag.

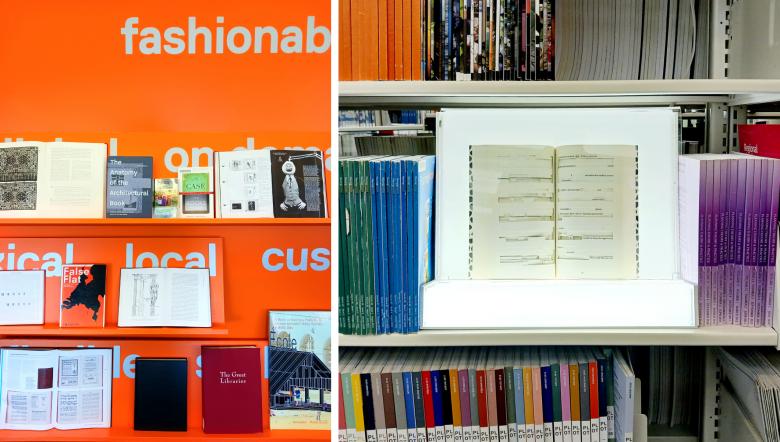

Perpendicular to the vitrine is yet another display, an orange wall titled “Future 2023–” and displaying library books in front of some terms apparently teasing the book's future: temporary, fashionable, accessible, custom, artistic, indexical, graphic, … The books, most of which visitors can actually handle, are related to the instructors/curators (Countryside, A Report), are about books (The Anatomy of the Architectural Book by André Tavares), or are by architects who are as cognizant of the power of books as Corbusier and Koolhaas (Flesh by Diller + Scofidio, A Book on Making a Petite École by MOS). What this collection of books says about the future of books is unclear, up to the viewer's interpretation.

Other clues as to the findings of the students and instructors on the future evolution of books are found, firstly, in the stacks one level down, where a lightbox displays Jonathan Safran Foer's Tree of Codes. Published in 2010, the “sculptural object,” in the words of the publisher, has a different die-cut on every page. Technically it is two books in one: “I took my favorite book, Bruno Schulz’s Street of Crocodiles,” Foer has said, “and by removing words carved out a new story.” Part art book, part literature, Tree of Codes would be a singular object in previous ages, but it is a practicable, if scarce and expensive, book in the age of globalization.

Secondly, returning to the large book at the start of the exhibition, one of the pages in volume three states: “The future book is local. It is made from locally produced materials, printed nearby, and delivered to a homegrown readership. Hyper-local publishing will lead to a renaissance of book innovation.” The text is not credited, but I imagine the words are Irma Boom's. Even if the words are not hers, Boom's stamp is found throughout the exhibition; much more than Koolhaas, whose influence on the form and content of architecture books over the last thirty years is undeniably outsized. Boom is a graphic designer, but she is also a bookmaker, interested in the way books are made, sit on the shelf, and are read. A focus on the book as a physical object pervades the exhibition. As such, the future of the book as something physical, not digital, is hardly in doubt — the shapes it takes is another story.

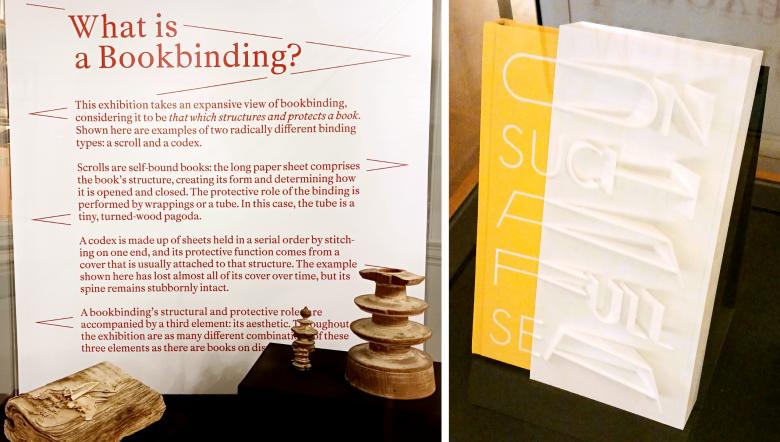

As an addendum to the above review of The Book in the Age of …, anyone heading to Harvard University to see the exhibition at Loeb Library is encouraged to also stop by the nearby Houghton Library to see At the Limits of the Book: Bindings from the Houghton Library Collections, whose contents have considerable overlap with the exhibition by Koolhaas, Boom, and Denny.