Project Location

Surrey, United Kingdom

Topic

Users

Community, Social interaction

Program

Social welfare

Community

From Domestic Abuse to Social Housing

the stage is set itself a tool of force curtained to provide both privacy and power to every violent scene; the cast of two – abuser and abused and those outside, with minds averted, waiting in the wings. Interval

Having personally conducted interviews with survivors and experts of domestic abuse, I have become increasingly aware of the degree at which abuse takes place within the domestic space. Using new frameworks for practice, forming a cyclical engagement between legislation, survivors, experts and architectural design, this project with the architect as translator, questions: By acknowledging abuse itself as wholly the responsibility of the perpetrator, what role has architecture played in the events of domestic abuse? In the process of escape from abuse? And what role is architecture able to play as a support in the recovery for the abuse survivor?

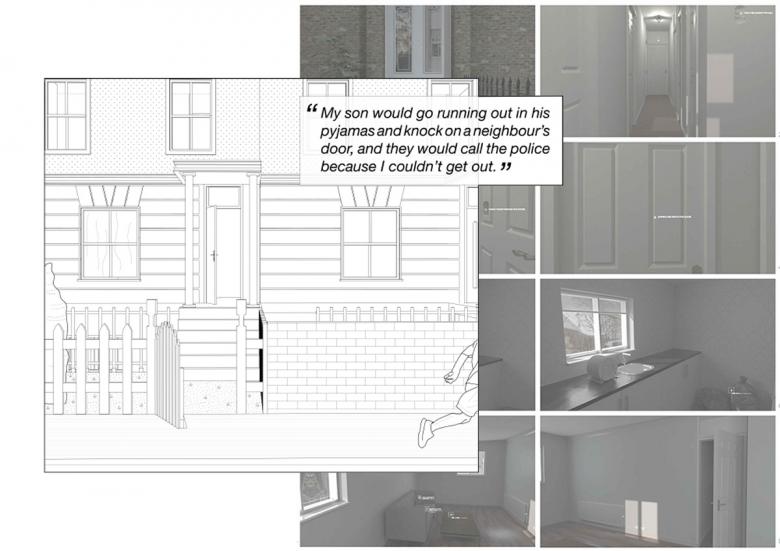

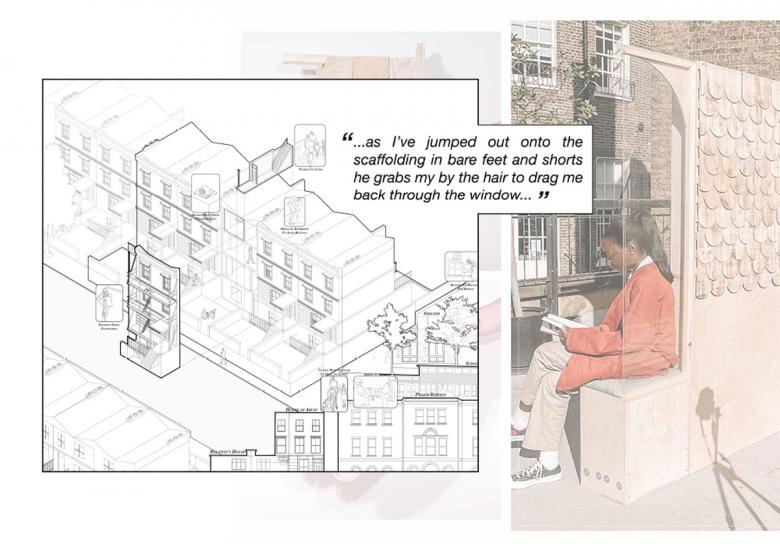

‘once he really really shoved me in the kitchen and the corner plinth on the old cabinets went right into my back and cut all my back’ – Interview with SD (Jan 2022) In response to interviews with survivors, the project works across three stages that architecture inhabits in domestic abuse. 1. The home as a weapon in abuse, focusing on how architecture is used to inflict harm. It is not suggestive that architecture is a reason for harm, but instead, through forensic analysis, that the acts of crime taken place form architectural patterns. The interviews show the use of architecture as a weapon and are best understood by analysing real-life experiences in abuse. 2. The role of neighbourhood in escape from abuse. With events of abuse demarcated by perimeter walls, the surrounding set-up plays a significant role in providing safety to escape. The role of the neighbour, the stranger, the school and the family form crucial characters in the initial stage-set for recovery. Many of the survivors have only escaped due to the support from local the community. Despite this reticent involvement taking place as brief encounters, the support provided is largely hindered or aided through architectural planning. 3. The role of architecture as a pre-condition for post-abuse recovery. In response to interviews, the project redesigns existing triggers of post-abuse living and proposes a series of retrofits to the current social housing typologies (provided by the 2021 Domestic Abuse Act). Using predominantly a low-cost timber construction, the proposal redesigns the standard typology and establishes an architecture of care that uses height as a threshold for safety, shared facilities, allotments, non-typical windows, soft wall claddings and split-level staircases. It is architecture that provides the stage set for domestic abuse; it is architecture that provides the tools of violence for abuse. It is therefore imperative to recognise the role of architecture in domestic abuse and the role it must undertake to become an architectural antonym, transitioning the house from a place of violence, to a home of refuge.