Couldrey House

I designed the Couldrey House for a member of my family in Australia (completed Jan 2020). The house takes an unusual approach to making residential architecture in the Australian landscape.

Many houses there tend to hover over the ground with lightweight materials which need re-coating and replacement. I instead designed Couldrey House to spring directly from the subterranean rock and to be made of heavy materials lasting a very long time. The house continues the local tradition of catching cooling breezes with good aspect and a permeable layout, but boosts this with passive radiant cooling from thermal mass; almost unheard of in houses of sub-tropical Australia.

Location: Brisbane, Australia

Architect: Peter Besley, Assemblage

- Thanks to: Jessica Spresser, Max Blake, Andrew Furzeland

Builder: TM Residential Projects

Floor Area: 320 m2

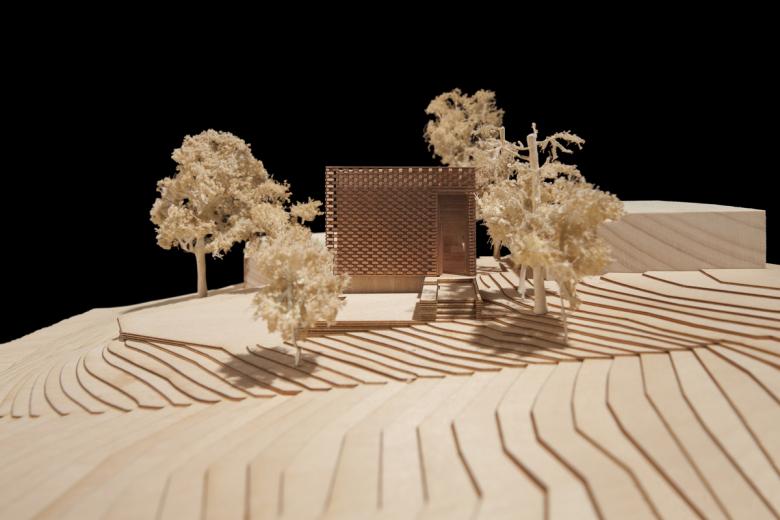

The site for the house is on a spur in the foothills of Mount Coot-tha in western Brisbane, a massif formed by granite movement in the late Triassic period. It is an ancient and enigmatic place, if not always seen so by people who live there. The house in some ways continues my work in the Levant, particularly Iraq. Buildings there seem aware of the scale and solemnity of the land in which they sit. The forms and spaces are compelling, but simple. They sit heavily on the ground. They seem to say to the landscape: “I can accompany you in your long journey.” There is a shared monumentality between building and landscape, even when that monumentality is intimate, such as in the houses. Through them I have become particularly aware of the deeper, haunting quality of ancient landscapes of which Australia is one. The architecture of Couldrey House is designed to allow visual noise to fall away to heighten awareness of these qualities.

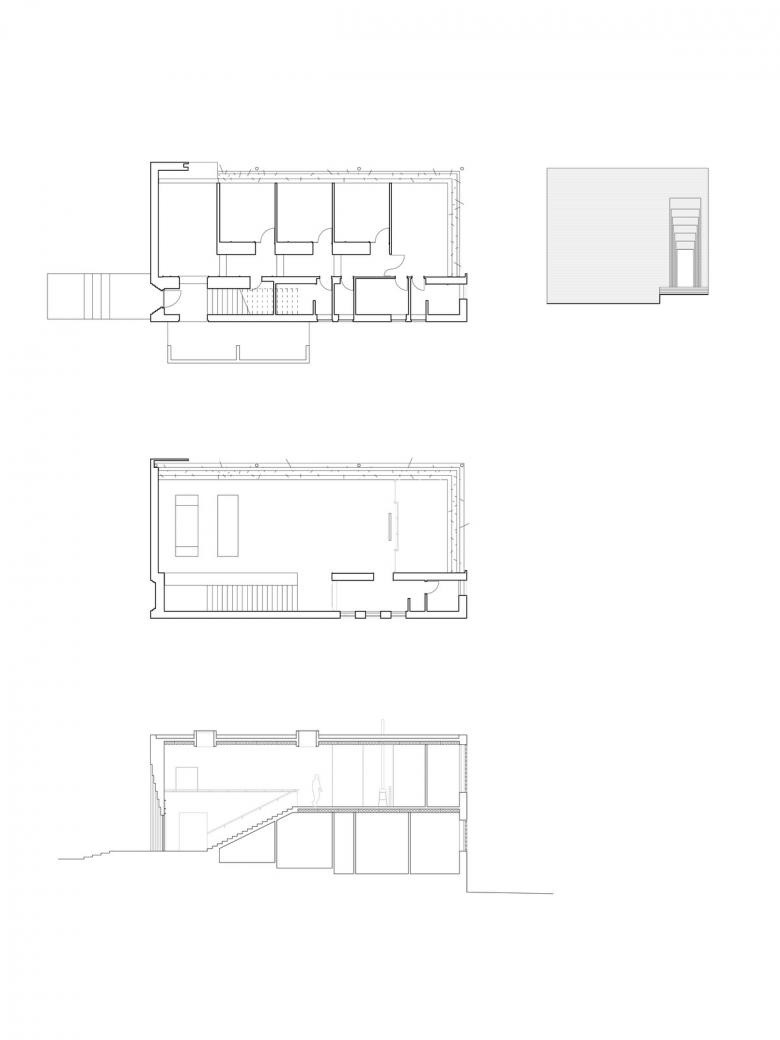

Using masonry was an early decision. The building is designed to be immensely heavy. The climate in this part of Australia is evolving: it is now hot/dry as much as it is hot/wet. A hybrid approach to cooling may now come into play, beyond the traditional reliance on intermittent breeze only. The house is designed to create radiant cooling using thermal mass via 30 nine-meter-long precast concrete floor and roof units, each weighing nearly four tons. Diurnal temperature difference recharges the thermal mass at night, ready to cool the occupants each day. Radiant cooling does not rely on air, so supplements traditional convection cooling and humidity control.

Brick in Australia tends to have an association with mass low-cost suburban housing, but I use it differently. Europe and the Levant have a long and rich history of brickwork and the skill-base that comes with it. Brick is considered a quality material worthy of the attention of leading architects. Around the great mass of the house I have wrapped a brick envelope, shaped in a simple rectangular prism closed to the west and south and open to views and breezes to the north and east. I chose a thin, long off-white brick and complemented this with a matching white mortar. No windows are made in the elevation to the harsh western aspect, in this case also the street frontage. The brickwork is instead folded in concertinas in a scale play around the main entrance door, which catches the afternoon sun.

A similar concertina of brickwork stretches horizontally in the form of a set of large approach stairs, this time with their brick extrusion holes exposed for drainage. To the south, I cut large slots horizontally into the facade to create masonry “louvres”, giving both shading and privacy. The house has parapet walls and no overhangs, its flat internally draining concrete roof piled with stones. The roof has a “plug and play” nature where various paraphernalia such as antennas, satellite dishes, solar hot water tanks, photovoltaics, and so on can be added or taken away as technology changes, with no effect on the house whatsoever.

The overall effect of the envelope is sober, and somewhat other-worldly. The masonry was important so the building’s character develops and becomes more nuanced as it weathers and ages, and does not require continual replacement in order to look “new”. The building should get better, not worse, with time.

A distinctive feature of my brickwork design is the extruded mortar “snots”: the approach of allowing excess mortar pushed out of the joint in the laying to remain, and to not strike it off. I wanted this for several reasons: the snots are expressed in the bed joint and not the perpend, giving a strong horizontal effect, like corduroy. It has the effect of unifying the brickwork, which otherwise presents as its standard unitized, cellular self. Secondly, the projections of the snots catch the strong sunlight and create a visually complex play of shadows. The shadow play is an important part of the ornamentation system of the building. Lastly, the snots are highly irregular, unlike the bricks, and together the textural effect is striking, and starts to form aesthetic allegiances with landscape features. People have likened the brick elevations to tree bark, for example, or sedimentary rock. Children prefer to see it as cake with icing.

The actual layout of the house is simple, but reverses the standard floor plate arrangement: common spaces are placed above and bedrooms below, so together with the siting and very tall ceilings gives the occupants a feeling of living high up amongst the tree canopy. This is reinforced by avoiding floor-to-ceiling glazing and instead terminating the tall windows at one meter above floor height. The effect is great openness but also privacy from the street below, and a “nest-like” experience for the occupant. The lower floor slab steps down with the topography, telling you about the landform, and allowing each bedroom to have it’s own floor and “address.”

A number of smaller masonry elements I designed during construction, in response to observations of the bricks themselves being cut, handled, and laid. The masonry screen to the wood fire place for example was composed of strangely split bricks first sighted cast off as waste in the site skip. Such things are impossible to draw; they are peculiarities of the physical material and need to be apprehended at 1:1 scale.

The completed house is something of a contradiction. It appears alien in the immediate suburban street yet kindred with the wider landscape, like an abstracted outcrop. The district has a scattering of monumental objects perched on spurs and ridges, which look out across the expansive land surrounding them. Robin Dodds’s St Brigid's church is visible to the north. The Euclidean form of a concrete water tower also rises up nearby. These objects feel like the house’s urban siblings.

The builder has finished but the house in a sense remains incomplete. The final “design” requires considerable time. Plants need to overrun the masonry envelope, not least from two 25-meter-long elevated planter boxes. The building stands waiting for endless cycles of weather to be cast down upon it, to gain the finer patinas of age. The mass of the house and its emphatic sense of permanence, the sobriety of its masonry, and the spareness of its form, all give a sense of serene indifference, a quality it draws from the ancient landscape it finds itself in.

Peter Besley is a UK architect and formed his new architecture and urban design studio in 2019. He previously led Assemblage in London which he co-founded, and taught at the Bartlett School of Architecture. Peter practices and teaches internationally.