Crafting Hansel & Gretel's Digital 'Breadcrumbs'

Hansel & Gretel, a collaboration between architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron and artist Ai Weiwei, opened at the Park Avenue Armory in New York City earlier this month. World-Architects spoke with iart's Valentin Spiess to learn about what went into making the space of surveillance a reality.

Installation: Hansel & Gretel

Location: Park Avenue Armory, New York City

Dates: 7 June to 6 August 2017

Artists: Jacques Herzog, Pierre de Meuron, Ai Weiwei

Curators: Tom Eccles, Hans-Ulrich Obrist

Technical Consultant: iart

Herzog & de Meuron and Ai Weiwei had collaborated on the high-profile "Bird's Nest" stadium for the 2008 Olympics in Beijing, but that commission hardly prepares one for their latest collaborative work. Located predominantly in the Park Avenue Armory's Drill Hall – a setting for groundbreaking, often immersive works by artists and the occasional architect – Hansel & Gretel is a darkened surveillance space that is strongly aligned with the increased use of security cameras in public spaces. But instead of paranoia or fear, the installation elicits joy, as visitors interact with the infrared cameras that paint the black, gridded floor with static images – digital versions of the fairy tale's breadcrumbs – that slowly decay back into darkness.

It takes about ten minutes between entering the darkened Drill Hall via a long, dark tunnel and getting comfortable with the installation's setup – this according to Spiess, the head of iart, a firm that works with artists and architects to realize complex, media-based projects, such as the "frieze of light" across the Kunstmuseum in Basel, where the firm is located. I would concur with this time frame based on my visit during a press preview the day before the installation opened; after getting their bearings, fellow journalists threw their coats down, lied down on the bowed floor, and spun around with their arms out to cover the floor with patterns of light.

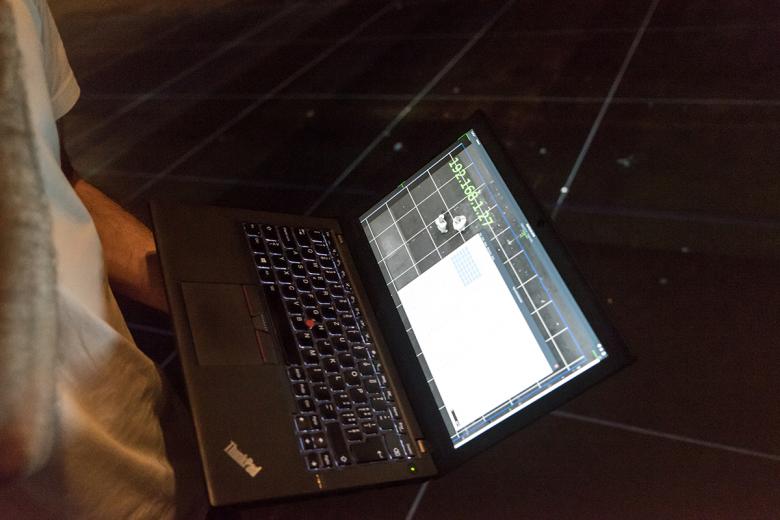

Things started when Herzog & de Meuron, also based in Basel, stopped by iart's office with the idea of tracking the movements of people in a darkened space and translating them into grid patterns across the floor. Through prototypes, an iterative process, and iart's willingness to "misuse" technology for artistic ideas, the project evolved into what could be called a performance piece, where visitors interact with surveilled "selfies" that are highlighted by red boxes that appear to hone in on important details. But how does the installation work? How are images taken and projected in a darkened space?

The key to the installation is infrared, a spectrum of radiation invisible to humans but visible to cameras that are set up to block visible light while capturing infrared light. To snap images and project them onto the floor, iart developed a surveillance system (the "iart tracker module") made up of a small computer coupled with an infrared camera and projector. An array of 56 modules cover the Drill Hall space. Combined with floodlights that function in the near infrared specturum and an algorithm that finds regions in an image that differ from the surrounding space, the modules enable visitors to be tracked without their immediate knowlege; the equipment is there, but it is tucked away in the darkness, invisible to visitors' eyes. But for those wishing to "fool" the tracker modules, Spiess explains to me, they only need to know how infrared works and wear clothes that appear visually black in infrared – though this does not mean black clothes.

The infrared is only about half the story in the Drill Hall installation. Of equal importance are the projections, which Spiess described as the installation's "random aspect" that necessitated a "really complex solution." A series of algorithms developed by iart addresses around thirty parameters on site, such as the optical exposure, the decay time of the images, and the location of the large illuminated rectangular patches where people tend to congregate. These algorithms run on computers with their own render units, in effect taking the camera images and outputting them after processing to the 56 projectors covering the 145 x 215 ft (44 x 65m) floor surface. The total projection is 7,850 by 12,360 pixels, which can be viewed online as a live-stream.

Not normally working on projects so "big brother," Spiess assured me that none of the images captured by the hardware and software that iart designed and developed is being stored – as soon as the images disappear on the floor they are gone forever. But with cameras overhead, not in your face like the second part of Hansel & Gretel, is there any danger in keeping the images? Facial recognition would work in the Drill Hall only if people looked directly up, after all. But with gait-recognition technology nearly a thing, it's not hard to imagine iart's technology being used to recognize and track people through their distinctive movements; or to consider the thousands of cameras already surveilling the city's streets doing the same thing. Such is the power of Hansel & Gretel: scratching below the surface of the participatory images reveals layers of commentary on the states of surveillance we find ourselves living in today.