Towards a Probiotic Architecture

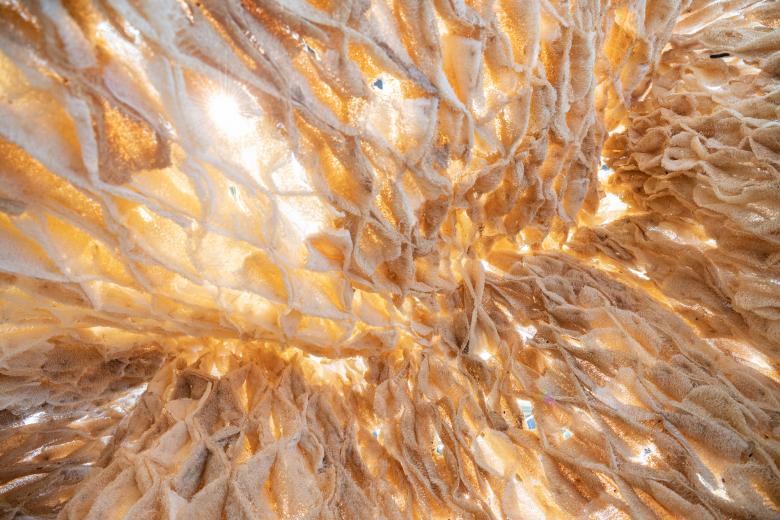

The Living's contribution to the 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale is "Alive: A New Spatial Contract for Multi-Species Architecture," an immersive installation made from luffa that asks: "What if we could change our architectural environments to be better hosts for a diversity of microbes and to decrease the amount of harmful ones?"

The installation by David Benjamin's New York-based design practice is found near the entrance to the Arsenale's long Corderie building, in a section of Biennale curator Hashim Sarkis's exhibition, How will we live together?, that is devoted to "living with other beings." Adjacent contributions, such as Philip Beesley and the Living Architecture Systems Group's "Grove," are ambiguous about what those other beings are, but Benjamin is much more precise in his target: microbes.

"Microbes are everywhere," he writes, citing that the human body has more microbial cells than human cells. Lucky for us the "good" microbes outnumber the ones make us sick, helping us digest our food and even form memories through viral DNA. Benjamin has a positive view of microbes in "the city" that is the human body, but he contends that "the ones that survive in our typical architectural environments tend to be the ones that have antibiotic resistance and enhanced virulence." In other words, our buildings and our actions in them — cleaning, disinfecting — may be hurting us.

So The Living's installation answers Sarkis's curatorial question with its own question about inverting the trend of "sick" buildings to create environments that foster the microbes that are good for us: "probiotic buildings." Benjamin's vision of the future includes "spaces for both humans and microbes," rooms with "different microclimates for many types of microbes," and HVAC equipment "supplemented by microbial reservoirs." Far-fetched, yes, but believable coming from the studio that successfully built an installation made from organic corn-mycelium bricks.

In this vision of the future, sponges like the luffa "Alive" is made from would serve as environments to capture and host microbes: the network of voids "create different pockets of shade, temperature, moisture, air flow, and nutrients." But how would the microbes that take to such environments be nourishing to humans rather than harmful to them? "Just as a healthy gut microbiome promotes to our individual health," Benjamin writes, "a healthy urban microbiome might promote our collective health." So diversity is key — with people, microbes, and all other beings.