Explaining, Mediating, Selling

What do architects think about important future issues such as climate change or digitalization? How do they envision a sustainable building culture? What solutions do they have? What framework conditions do they need in order to fulfill their tasks and responsibilities in the best possible way? To address these topics, World-Architects invited three offices — one from Germany, one from Austria, one from Switzerland — to each of a series of five virtual conversations that were transcribed and published online in the second half of 2020. The architects openly discussed the issues with each other and provided deep insights into their worlds of thought. How can clients, craftsmen, neighbors and authorities be won over to high-quality and sustainable architecture? Fränzi Essler and Walter Waldrauch from the office raumstation in Starnberg discussed this issue with Sergio Marazzi from Marazzi Reinhardt from Winterthur and Matthias Hein from Bregenz.

Elias Baumgarten: Your offices raumstation, Marazzi Reinhardt und Hein architekten are active in and around Munich, in Zurich’s agglomeration, and in the Vorarlberg region; that is, areas which are currently experiencing strong growth. In terms of architecture, this is accompanied by numerous challenges, many different, sometimes contradictory demands on your projects: You have to densify the built-up area and preserve the architectural heritage, your designs have to be sustainable and should protect economic interests. We would like to know how good designs can be achieved in this situation.

Sergio Marazzi: The climate debate, which is finally gaining momentum in architecture, is adding a new dynamic and raising intriguing questions, including in conversion projects. The preservation of monuments has taken on an additional dimension, one not always compatible with preservation objectives. It is imperative that we build in a more sustainable and environmentally friendly way, but at the same time we want to preserve our architectural heritage. As a society, we therefore urgently need to agree on which priorities should be set, when, and where.

Matthias Hein: First of all, we need to discuss what sustainability actually means. Discussing the thickness of insulation and energy savings is all well and good, but that alone will not get us any closer to achieving our objectives. I thought it was interesting what Lilitt Bollinger, Stefan Marte and Max Otto Zitzelsberger said in the interview with you, Elias: We have to abandon the throwaway mentality that is prevalent in the building industry. We should maintain and adapt buildings. If we do build new ones, the buildings should be designed for long life cycles and not end up as hazardous waste after a relatively short time. And we should focus on regional value creation and short distances.

Walter Waldrauch: The building physics specifications are sometimes problematic, especially for conversions. When, for example, arguments arise over how many centimeters of roof insulation is on a historic house, you wonder how useful all the regulations and charts really are. I would boldly say that some measures are less useful than building physicists tell to us. We architects are often forced to spend too much time on fulfilling sometimes contradictory requirements, time that is lost for designing.

MH: I see it more positively: most things work out if the clients want them to. For example, we were commissioned to design the kindergarten in Muntlix in the Vorarlberg municipality of Zwischenwasser. The brief specified that sustainability should be considered down to the last detail. Our wooden building meets the passive house standard. The construction material was cut in the community forest, all transport routes were very short, and the craftsmen were locals. At the request of the community and the pedagogues, we installed a nine-centimeter-thick rammed earth floor, for which excavated material was used. Now nobody complains about holes in the children’s trousers from playing or when a table wobbles on the uneven surface. No one is asking us to be liable.

SM: I think it’s very important to involve the client. We recently completed a conversion in the Töss Valley in the Zurich Oberland. Today’s ideas of building physics were invalidated in this project. There is only minimal heating, no additional insulation; not all the rooms are homely in winter. But the residents are happy to live in such an original house.

Fränzi Essler: These are nice stories, but they are about luxury situations. We are not in such a comfortable situation. About 80 per cent of homes we build are condominiums. Behind many buyers is a surveyor. Any deviation from standards and building laws immediately causes trouble and stress. Our challenge is to create sophisticated architecture in spite of all the specifications and regulations and in compliance with the requirements of specialist planners; architecture that people still like to look at and that is not simply the "spatialization" of regulations.

SM: You’ve got me wrong, Fränzi. We also have to comply with standards and building laws for the most part. What I’m getting at is that you have to engage in a constructive dialogue with the client, the neighbors and the authorities if you want to push through ambitious architecture.

WW: I agree, but how do you do it? We are noticing that people interfere more and more often and always give more weight to their personal interests. Today, almost everyone feels the need to have a say, even if a project only marginally affects them or they are not familiar with the subject matter at all. In Bavaria, there has been a citizens’ initiative against almost every building project in the last five years or so, and one has to constantly fight legal battles. The approval processes have become extremely time-consuming. I would like to see the sometimes selfish demands of individuals taking a back seat more often to the interests of the general public.

SM: We seek exchange before we officially apply for a permit. Communication is essential. Sometimes a model and an information evening with the neighbors is right, another time a good conversation over the garden fence works. In this way, you can reduce a lot of friction and reach 90 percent of the people. Of course, there will always be those who patiently listen to everything, politely thank you and then raise an objection. This is another reason why I advocate regional building: Over time, you get to know the people in your city, in your region; you understand their mentality and can build up a relationship of trust.

EB: The clients of many architects are property developers and project developers. They do not have the best reputation on the scene. Complaints are often made that they are particularly responsible for mediocre architectural quality and boring self-standardization in residential construction.

FE: My father worked as a property developer. We worked for him a lot at the beginning of our career — even in sales. We still do plenty of planning work for property developers. Ultimately, what is offered is what the market demands. What is really missing is an awareness of architectural culture among end consumers.

SM: Yet you still manage to create outstanding architecture. How do you do that? How can you convince building contractors?

WW: Despite all the complaints, there are positive developments: Well-designed, durable and sustainable buildings have recently become easier to market. All of a sudden, it also makes sense from a purely economic point of view to accept higher construction costs. This makes it noticeably easier for us to convince people.

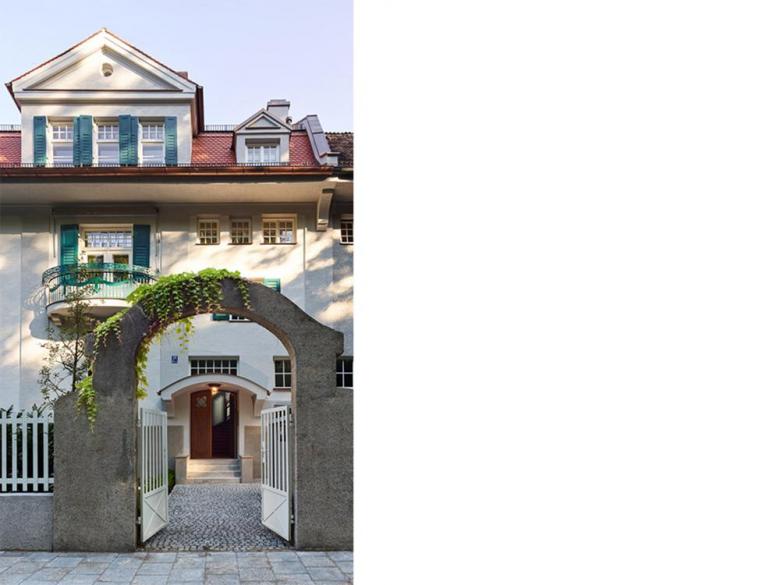

FE: We are currently working on the conversion and renovation of the listed Derzbachhof, the oldest farmhouse in the Munich city area. It is a project of the Munich-based developer Euroboden; the concept was developed by our colleague Peter Haimerl. The historical farmhouse is being restored and is to include community rooms and flats. Behind it, we are constructing a new residential building. The complex will be ideal for families, who will grow vegetables in the garden and keep small animals. This is possible because our client has long understood architectural quality as a selling point and has been very successful with this approach. I am confident that this will find more and more imitators.

MH: I can endorse Walter’s words. We were asked to design a small residential complex in Götzis and made it a condition that we use wooden windows and, above all, build without external thermal insulation. Our client, a Vorarlberg property developer, agreed despite initial reservations and realized that he could sell this concept well. In the meantime, he commissioned us to build a second complex based on the same principle, and I was asked to talk about sustainability in architecture in the sales brochure. The prospect of economic success can bring about a rapid change in thinking. We architects sometimes find it hard to bring ourselves to vent such arguments, but they are very helpful in bringing about positive changes.

EB: Fränzi, you mentioned that there is a lack of awareness of good architecture among end users. We hear that very often, and it was also deplored in our two previous D-A-CH talks. So, what can be done about it?

FE: First of all, we have to address political decision-makers. Here in Starnberg, it is not a committee of experts that decides what may be built, but members of the elected city council, the so-called urban planning committee. All kinds of professions are represented on this committee, but practically no architects. Most of the committee members have no expertise, they argue according to their taste or represent their particular interests. Basically, it is already clear before the debates what each member is going to say. This is where we should start, for example by organizing tours for the committee members through the district to explain why certain buildings are architecturally successful and others are not. We would like to implement this idea in the future.

SM: We architects are in a bubble — as we are in this round-table discussion. Moreover, we only design a small percentage of the built environment. That’s why I think it’s important to already convey building culture to schoolchildren. In Switzerland, our professional associations SIA (Swiss Society of Engineers and Architects) and BSA (Federation of Swiss Architects) together with the non-profit association Archijeunes, which works to raise awareness among young people through workshops in schools, have taken the initiative.

MH: Talking about a bubble, Sergio, I think the most important thing in communicating architecture is the language. A lot of things are in a sorry state here. We architects have become accustomed to our own way of expressing ourselves, which outsiders can hardly understand and which they sometimes even find alienating. One of my friends is a writer, and he says that our technical jargon scares the devil. That's why I really like the fact that the Vorarlberger Architektur Institut (vai) has been regularly explaining buildings in generally understandable language in a weekend supplement of the daily newspaper Vorarlberger Nachrichten since 2011, thus reaching many people and getting them interested in the discourse. I would like to see more such projects.

SM: I am on the board of the Winterthur Architecture Prize. Again and again, I criticize that it is an award by architects for architects, a major back-slapping once every four years, often awarding the same projects several times. It would be great to move in the direction of communicating building culture, to show a project every year and to present it comprehensively to the public in the daily press. It is difficult to get through to the architects’ guild with these ideas. Gradually, however, something is happening here as well.

EB: We’re all the more pleased that you keep working on the topic of architectural communication and that you continue to stand up for architectural culture. Thank you for the open discussion.

Walter Waldrauch grew up near Vienna. He studied architecture at CVUT Prague and TU Vienna. He worked for Mergenthal and Mikado Architekten in Vienna.

Sergio Marazzi completed an apprenticeship as a carpenter before he was self-employed. After an internship at the architecture firm Hopf & Wirth, he decided to study architecture at the ZHAW. In 2004 he founded Marazzi Reinhardt, a joint office with Andreas Reinhardt, in Winterthur.

Matthias Hein studied architecture at the University of Innsbruck and the Vienna University of Technology. In 2002 he founded his own office in Bregenz. He is involved in the design advisory boards of Kirchheim unter Teck (Germany), Langen bei Bregenz and Weiler.

This article originally appeared as "Erklären, vermitteln, verkaufen" on Swiss-Architects. Translation by Bianca Murphy.